|  |

By Greg Niemann

Spanish Padre Juan de Ugarte was more of a folklore hero to Baja California than Paul Bunyon was to the U.S., more real in fact - Ugarte really existed!

As far as individual effort and tangible results by a Spanish missionary in Baja, Ugarte’s name heads the list. Honduran, he was born in Tegucigalpa in 1660, and became Chair of Philosophy at the esteemed Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo in Mexico City.

Regarding the California development, Ugarte became involved in everything. He solicited funds; he established missions; and he instilled many practical innovations.

His boss Padre Juan Salvatierra, President of the California Missions, later glowingly wrote of Ugarte, “...he was the Atlantic, the Pillar of California, to whom after God is due the conversion of the Indians of these Missions.”

A Bear of a Man

By all accounts, Juan de Ugarte was a bear of a man. He was over six feet tall, enormously strong, large in stature, and even larger in legend.

As Treasurer of the Pious Fund, Ugarte spent several years banging on doors to obtain donations and support. In 1697 Padre Salvatierra was sent to establish the first Baja mission at Loreto, and Padre Francisco Piccolo received the second one at San Javier (Xavier) in 1699.

Ugarte finally got a California assignment but needed transportation. So he repaired a shipwrecked longboat and crossed the gulf in a storm, arriving at Loreto on April 1, 1701.

A colleague second-guessed Ugarte’s Baja decision by writing, “Here is a gentleman, raised amid comforts of a wealthy home, now reduced to a tedious and burdensome life...a man of letters and highly esteemed in the schools and pulpits of Mexico, a man of sublime genius, voluntary condemned to associate for thirty years with stupid savages.”

Ugarte immediately headed into the mountains to take over Mission San Javier which was deserted because of a threatened revolt. After he arrived with his escort of soldiers, he found the Indians wary of their presence. So he sent the soldiers back to Loreto and confronted the Indians alone.There were murderous threats from some natives unwilling to become docile converts. There were thefts, deceptions, and insincerities. At first the natives who sat for Catechism classes used to howl with laughter when Ugarte would mispronounce a Cochimi word, even giving him absurdities to repeat rather than the correct word.

Once, on a cold winter’s day he began preaching about the hellfires of damnation that awaited sinners. His sermon was disrupted by bone-chilled natives as they crowded around him wanting to know how they could go to this warm place. The fires of hell sounded rather comforting to them!

Ugarte commanded respect among his charges. He also earned it. In one incident, the natives confessed to being so terrified of mountain lions that they had determined the animals were gods. This made it tough when Ugarte tried to convince them that his was the only true God.

The mountain lion god

One day he and some Indians came across a mountain lion. Ugarte stoned the lion, dazing him, and then choked it to death with his bare hands. He threw it over the saddle of his burro and returned to the village. To complete the symbolism, while the villagers watched, he skinned a portion of the meat, cooked it and ate it. That night the Indians ate the rest of the meat. There was never another argument about the “godliness” of the mountain lion.

Ever practical, Ugarte planted cotton and brought over sheep and goats from the Mexican mainland. He hired a weaver to come and teach the Indians to weave cloth to cover themselves.

Ugarte cleared land and planted corn, wheat, and beans. He established orchards of olives, pomegranates, figs, citrus, grapes, and dates. He was the Padre who first introduced the “mission” variety of wine grapes to the Californias.

He dug an elaborate irrigation system and built dams and canals to nurture the newly-planted crops.

At Mission San Javier he established the first school for indigenous children in the Californias, a seminary to teach boys; girls were taught in a separate building. He established California’s first hospital and care for the aged. He journeyed to neighboring Indian settlements further spreading his religious beliefs.

Ugarte traveled widely. In 1706, with Padre Jaime Bravo, 12 Spanish soldiers, and 40 Yaqui Indians, he made an expedition to the South Sea (Pacific Ocean).

Juan de Ugarte succeeded Salvatierra as President of the California Missions in 1719. Earlier he had saved the entire California mission project by convincing Salvatierra not to give up during some very trying times.

Ugarte needed a ship for exploration and to ferry supplies, but none was available. Small matter to an overachiever like Ugarte. He’d build one!

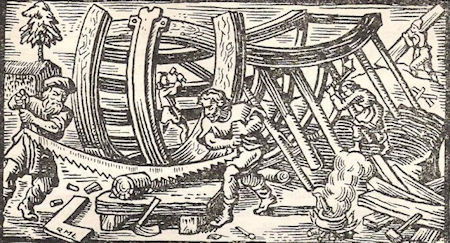

Finding wood in Baja California big and sturdy enough to build a ship was a challenge, but Ugarte prevailed. About 50 leagues (150 miles) northwest of Loreto (site of a later mission named Guadalupe) were some large trees of a hard wood called guaribo, or guirivo.

The resourceful Ugarte hired a shipbuilder from the mainland, grabbed some soldiers and some Indians and headed off into the mountains. They not only had to hew the timbers, but they had to cut a trail so that oxen could haul the wood down to the estuary at Mulege where the bark-balandra was built.

California’s first ship builder

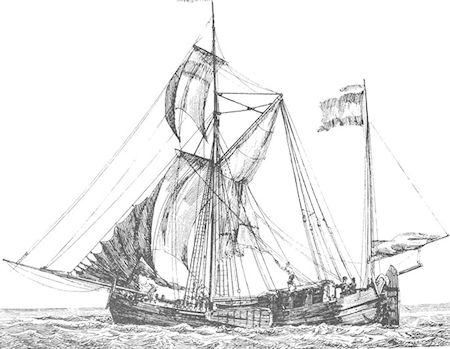

Ugarte called the ship “Triunfo de le Cruz” or “Triumph of the Cross” and launched it on Sep. 14, 1719. That first ship built in the Californias was immediately considered the most beautiful, the sturdiest, and the best constructed sailing vessel ever known in California. It was used many times to cross the Sea of Cortez.

In 1720 Ugarte sailed his new ship from Loreto to La Paz, taking Padre Bravo with him to establish a mission there. Ugarte stayed at La Paz three months making friends with Indians, even those who were normally hostile. The mission secured, he returned to Loreto in January 1721.

Ugarte had dreamed of establishing a land route from Sonora, Mexico, past the Colorado River and down to the Baja missions. In 1721, he took “Triunfo de la Cruz” north to the tidal bore that enters the Colorado River and then south along the Baja California coastline, thus also assuring that California was not an island.

While Juan de Ugarte’s exploits affected so many so profoundly, his brother Padre Pedro de Ugarte, also a missionary, served in a less conspicuous manner. Pedro ended up in charge of Mission San Juan Bautista Ligui where he spent five years. Because of poor health, he left California in 1710.

Energetic Juan, however, rarely rested even though he suffered from an asthmatic cough in later life. When urged to slow down and retire, he said, “Rest and quiet make me suffer more.” The legendary President of the Missions died in bed at San Javier in 1730 at the age of 69 and was buried there.

Later, in 1757, Jesuit Padre Miguel Venegas wrote, “Not without reason did Salvatierra name Ugarte ‘The Apostle.’ Untiring, he led in everything, did everything, undertook and succeeded in everything...”

The accolades continued

Continuing in the same vein, in 1787 Jesuit historian Francisco Xavier Clavijero wrote glowingly about Ugarte, “...nature blessed him with an illustrious birth, a phenomenal physique, a sublime mentality, keen ingenuity, a facility for arts and sciences, rare industry, prudence in economic matters, great magnanimity, a man superior to all obstacles and dangers, with meekness of spirit, while zealous in saving souls for God.”

In The Mother of California (1908) author Arthur Waldbridge North concluded, “Let Ugarte be remembered not only as a man of fine physique, the first shipbuilder in the Californias, but as an ardent Christian, a wise old diplomat and a fearless explorer. He stands forth bold, shrewd and aggressive, one of the most heroic figures in early California history.”

The Mexican historian Pablo L. Martinez in his 1960 landmark work A History of Lower California continued to highlight Ugarte’s eminence: “Ugarte raised the first regular crops... this enterprising man...exerted himself to remove stones to clear the space needed for planting. He planted the first vines and produced the wine that was consumed in the missions.

Lower California would do well to proclaim as a type of public-spirited citizen the venerable Padre Juan de Ugarte.”

Even historian Harry Crosby in his 1974 book The King’s Highway in Baja California added, “One of the great feats in Baja California mission lore is the labor of Padre Juan de Ugarte, a legendary strong man. He and his Indian charges brought 160,000 mule-and-burro loads of earth up the arroyo and filled in the side canyon at San Miguel (Comondu) to create acreage for agriculture.”

It’s extremely rare for someone to be so acclaimed for more than two centuries, but historians continued to single out the deeds of this enterprising padre. It appears there really was a Paul Bunyon in Baja—he seemingly was larger than life and his name was Padre Juan de Ugarte.